|

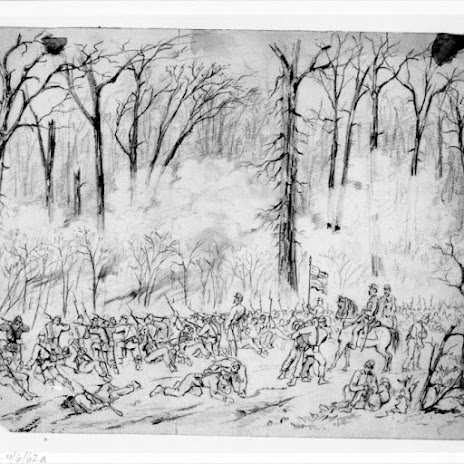

| “April 6, 1862 – The woods on fire. The 44th Regiment. Indiana Volunteers" in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper Sketch by artist Henri Lovie |

Samuel Andrew Baker[*] - like most of the soldiers serving in the War Between the States - wanted more letters from home.

Unlike most of his comrades, however, the eighteen-year-old Baker – serving in Company E of the 44th Indiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment – decided to create a demand for HIS letters by delivering “kernels” of information that would prompt return letters requesting – as Paul Harvey used to say – “the rest of the story.”

Here’s a letter to his father, Joseph Warren Baker on January 28, 1862, a couple of months into his service. Note his opener:

Dear Father I take my pen in hand to inform you that I am well at the present with the exception of a large boil on my forehead and I hope that these few lines may find you and Nancy well

There’s the first “kernel” – his oddly located boil. Baker followed that with a “poor me” line that went for the heartstrings: “I have been expecting a letter for a long time but I have to look on and see the rest of the soldiers get their letters when the mail [comes]”

Now back to another tidbit:

Our Lieutenant Col has been sick ever since we left Henderson [KY] and has now gone home on furlough and I expect that he will bring back some deserters when he get back here.

Since the regiment was formed entirely of Indiana men, and his company was recruited from the same community in which his dad and Nancy lived, Baker’s unfinished “deserters” comment would prompt their curiosity as to who had quit and if they knew them. Hence, another question to be answered.

Shrewd guy that Baker!

After some news about no pay, he told about his ‘piquet guard‘ experience the night before. But the way Baker spun it into a mystery in just a few sentences proved that he was a good storyteller – and tactician.

He first opened his story with background – a dramatic background with tension:

We have been expecting an attack here every night for along time and we have cut down the timber in a circle clear around the camp in a pile and every way crossways and every other way to keep the rebel Cavalry out and we have dug intrenchments and throwed up breastworks to plant canons.

Then he launched his story about lights and bells - with an element of comedy relief.

Yesterday and last night our company was on piquet [picket] guard, out about 2 miles from camp. Last night about midnight there was a light discovered across the road which showed itself about a minute and then disappeared as suddenly as it came. directly after ward the tinkling of a bell was heard for about three times. There was squad of men went out to discover what it was and after scouting around for a little while one chased up an old coon that had a bell on her neck.

Baker then added more dramatic tension back into his story with: “but [that] did not account for the light.”

a bout an hour afterwards the piquets was fired upon and the light appeared again and was immediately afterwards. There was a party of men went out to see what was up but did not find anything.

But Baker wasn’t done yet: “A while afterwards our men saw the light again”; then came the quick ending, “and fired three shots at it after that there was no more alarms in the night.“

What were the lights from? Confederates? Civilians? Matches? Fireflies? Did they quit because the source was dead? What? Baker never resolved that part of the mystery. It certainly would give the folks back home something to wonder about, discuss, form opinions, and then write back to him for resolution.

But it was his ending that was a classic “carrot-on-a-stick”:

There is a great many things I could find to write about. there is not room so I will have to cut it short off. Ever remaining your affectionate Son Samuel Andrew Baker [**]

Leave 'em hangin', Sam!

There are a million stories from the Irrepressible Conflict. This was just one of them.

Mac

Works Cited

[*] Samuel Andrew Baker, Co.E, 44th Indiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment, served from 1861 until he was killed in a railroad accident on January 30, 1865, as two cars of the train carrying the regiment were thrown off the track when the weight of the train loosened the rails. [2]

[**] Drawing that heads this post depicts the Battle of Pittsburgh Landing at Shiloh, Tennesee. It is from Frank Leslie’s illustrated newspaper May 17, 1862 , front page. The drawing by artist Henri Lovie was captioned: “April 6, 1862 – The woods on fire. The 44th Regt. Ind. Voltr. Col. H.B. Reed commdg. [Union] Left Wing near the Peach Orchard.” The regiment was engaged both days at Shiloh, April 6–7, 1862 and suffered 33 killed and 177 wounded.

In the below-cited regimental history, Rerick also told how the regiment earned its nickname at Shiloh: “a captain of one of the retiring companies of Wisconsin soldiers, said the Forty-fourth “fought like iron men–they wouldn’t run . . . it stuck, and for a long time the Regiment was known as the ‘Iron Forty-fourth.'” [2]

[1] “Letter, Samuel Andrew Baker in South Carrolton, Ky. to Joseph Warren Baker in Whitley County, Ind”. Samuel Andrew Baker Letters, Digital Collections, American Civil War Letters. University of Tennesee Knoxville Libraries.

[2] Wiseman, Becky. “Roll of Honor – Civil War – May 28, 2007” Whitely County [Indiana] Kinnexions blog, and Rerick, John H. (1880). The Forty-Fourth Indiana Volunteer Infantry: History of Its Services in the War of the Rebellion and a Personal Record of Its Members. Ann Arbor, MI: The Courier Steam Printing House. p.117.

No comments:

Post a Comment